Beyond policing

Amidst the public outrage around the murder of George Floyd and police abuse, many are once again focusing on “bad apples” and the need for police reform. But the cause of abuse or brutality isn’t bad training, bias, or lack of accountability. It isn’t a few “bad apples.” The problem is policing itself.

This post was co-authored with Quyen Ngo. A shorter version of this post was published in Newsweek

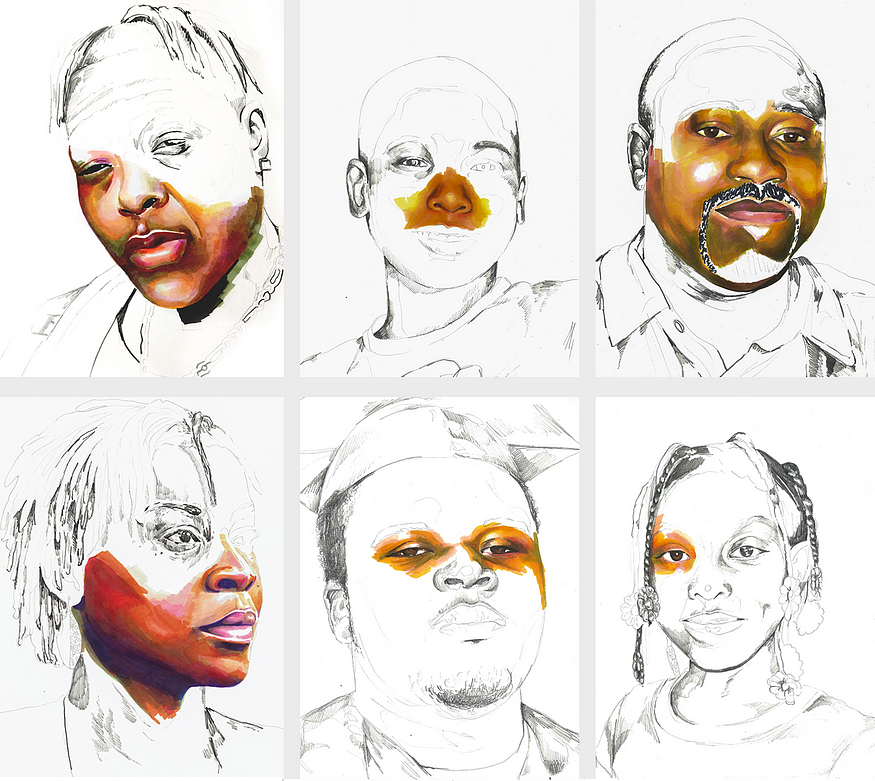

Art from Stolen Series. by Adrian Brandon (@ayy.bee). Adrian honors victims of police violence by coloring one minute for each year they lived. Top (left to right): Tony McDade, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott. Bottom: Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Aiyana Stanley-Jones

Art from Stolen Series. by Adrian Brandon (@ayy.bee). Adrian honors victims of police violence by coloring one minute for each year they lived. Top (left to right): Tony McDade, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott. Bottom: Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Aiyana Stanley-Jones

Amidst the public outrage around the murder of George Floyd and police abuse, many are once again focusing on “bad apples” and the need for police reform. Perhaps more than ever before, police leaders across the country are speaking up to condemn the horrific killing. Many are welcoming instances of police officers kneeling with protesters as “a step in the right direction.” But what exactly is “the right direction”? Is it, as Obama suggests, returning to the system at hand and implementing reforms — better training, more accountability, more diverse police forces? Or is it moving toward a new model — rethinking policing altogether?

Blurred lines in policing

Modern policing emerged in the eighteenth century as a means for power-holders to assert control — whether that be patrols preventing slaves from congregating, colonial police maintaining foreign occupation, or state authorities squashing mine and factory strikes. Police forces were formed to maintain the status quo through social control, keeping public order, and protecting people and property. They were built to quell riots — to deal with situations not unlike what we are experiencing in this moment.

This blurred line between public order and social control has shaped police forces to this day. Today, few know about the origins of policing as riot and slave patrols; policing is seen by many as a noble cause. Children want to grow up to become officers. Young men and women join police departments aspiring to “serve and protect” all, regardless of color or creed. The police have captured the public imagination as guardians of the community — a powerful image that forces many to cast off abuse, across both the ranks of the police and the public at large, as unfortunate exceptions.

But modern policing is a far cry from that idyllic image. “Policing” means to control, to regulate. It is the deployment of men and women, almost always from outside the community, armed and trained for confrontation, to “handle” any and all issues. A counterfeit bill? Call the police. Witnessing a mental breakdown? Call the police. Someone rear-ended your car? Call the police.

Banking on infallibility

The bulk of police training is spent on firearms and self-defense, on preparing for confrontation. A full fifth of officers are war veterans, bringing with them a military mindset. In theory, force is only to be used when the officer’s life is in danger. But the practice is more complex. In carrying the badge, officers are granted the power to kill. Granting such overwhelming power means trusting all police officers to never lose their cool, never make mistakes, and have perfect judgment. Officers are expected to never act under the influence of stress, fear, or anger because the consequences are potentially fatal. But a system that banks on human infallibility is one that is disconnected from reality.

It is not surprising, then, that police abuse is so pervasive. Hundreds are killed by the police every year — a whopping 8% of all male homicides are committed by the police. For Native American, Black, and Latino men, the risk is even higher. But killings are just the more visible part of the problem. Being seen as a criminal, getting arrested, frisked, handcuffed, are among the daily indignities experienced by black and brown Americans. Most Black Americans fear the police more than they fear violent crime. LZ Granderson writes, “I was 12 when an officer placed his gun to the back of my head while his knee rested in the center of my back. I had been sent to the store to buy a gallon of milk. I came home with trauma.” Regardless of how much members of the police desire to provide safety, the reality is that they often traumatize the very people they have sworn to protect.

Wherever policing is present, so too are cases of abuse.

Yet under the guise of safety, policing has expanded to other areas of life, bringing with it the same trauma. School-based policing is one of the fastest growing areas of law enforcement. But while it has plenty of negative effects — for example, increased rates of suspensions and arrests — there is no evidence that policing improves the safety of children. Similarly, armed police now respond to mental health crises, leading to an “epidemic of people shooting at people with mental illness.” Wherever policing is present, so too are cases of abuse.

Ultimately, the cause of abuse or brutality isn’t bad training, bias, or lack of accountability. It isn’t a few “bad apples.” The problem is policing itself. It is granting someone the right to use force whenever they see fit. It is the fact that someone has the power — the authority — to kneel on someone’s neck until they choke to death. The problem isn’t that some officers misuse their power — it’s that they have this power in the first place.

Centering on community

The alternatives to policing are known. They’ve been tried, studied, and researched — and they produce unmistakable results. A congressional study found that opening drug treatment facilities “result[s] in significant reductions in criminal activity”: selling drugs declined by 78%, drug-related crime by 48%, and arrests for any crime 64%. Community programs tackling gang violence also have remarkable outcomes. In communities where “interrupters” (often former gang members) mediate between factions before or when violence flares up, shootings and gang violence have significantly decreased: 44% in Oakland, 50% in San Francisco, and 66% in Richmond, CA. Researchers also found that mental health services, for both juvenile and adult offenders, are highly effective at preventing a return to crime. For example, programs giving at-risk youth access to counseling and cognitive behavioral skill-building have decreased violent crime arrests by 50%.

Officers are expected to never act under the influence of stress, fear, or anger because the consequences are potentially fatal. But a system that banks on human infallibility is one that is disconnected from reality.

These programs, and myriad others in the same vein, have one thing in common: they do not involve policing. They do not use weapons, patrols, or surveillance, so excessive force is an impossibility. These programs instead center around health, care, and community. The task of building safety is shared among social workers, counselors, medical personnel, and psychologists. Many are members of the community itself, people who understand the conditions that give rise to crime, who do not see offenders as mere criminals but as neighbors, and as humans.

The end of policing

Because we are so accustomed to policing, to fighting violence with violence, these programs may seem soft, naive even. But the reality is they are far more effective than policing and considerably cheaper. The United States spends $100 billion per year on policing, with many cities dedicating over a third of their entire budget to it — not to mention $80 billion per year on incarceration. And research finds that reform attempts — themselves already costly — do not actually make a dent on addressing police abuse: bodycams have no effect on police use of force or citizen complaints against officers; more diverse police forces do not reduce police violence; and anti-bias training shows no sign of making a difference in the racial bias of officers. The cost of drug treatment facilities and community programs is dwarfed by the costs of policing, yet yield significantly better results.

Not only do reform attempts fail to make a difference, but they do not reduce policing. They actually expand it. In The End of Policing, Alex Vitale writes that “community policing, body cameras, and increased money for training reinforce a false sense of police legitimacy and expand the reach of the police into communities and private lives. More money, more technology, and more power and influence will not reduce the burden or increase the justness of policing.”

A new model

Of course, the deeper causes of crime and violence must be addressed. Inequality is the best predictor of murders, violence, and other crimes, so any long-term solution to our social woes must be anchored in building a more equitable and just system. But in the meantime, it is upon us to take immediate action and reduce the role and power of policing in our lives. Any and all efforts to fix the system must be coupled with the questions: does this expand the role of policing, or reduce it? Does this bring in more uniformed and armed men and women, or less?

The problem isn’t that some officers misuse their power — it’s that they have this power in the first place.

Already some are heeding the call for less policing. Just this week, the Minneapolis Board of Education voted to cut ties with the Police Department and end school policing. Around the country, groups are calling to defund the police and reallocate budgets to health and community programs. Many of us are having the difficult conversations, within ourselves and our loved ones, to question the need for policing.

Ending abuse requires rethinking how we view public safety, removing our blind trust from a system that does not serve and protect us all, and removing our faith from band-aid solutions to that very system. Ending abuse requires moving beyond policing.

George Floyd, by Adrian Brandon, Stolen Series.